Flaws of the First Chronicles

I wouldn't be referring to Covenant as a failure all this time if I didn't ultimately see it as a missed opportunity. Despite my admiration for the Chronicles as an attempt at a ethical project, a world-building exercise and a subversion of high fantasy, it's undone at the same time by some serious weaknesses.

Most of the Covenant-mocking I've seen starts with his use of language - it's the kind of book where both the characters and the narrator drop in words like 'inexculpable' and 'anneal' as casually as they can - which is to say not very. But I've read Poe, I've read Lovecraft. I can take this. And least Donaldson's trying to be creative with his clunkiness in a rather charming way.

The poetry is universally bad, however. This is one bit of Tolkien I wish he hadn't imitated.

But I have bigger fish to fry with my critical Earthpower (Critpower?).

Protagonist problems

Covenant is meant to be a troubled character - embittered, suffering from an incurable disease, and stunned by the health and truth of The Land. Donaldson loads his back-story - I think - with enough woe to make his dilemma believable.

But Donaldson has Covenant do something upon arrival in The Land in Lord Foul's Bane to further complicate his relationship with the fantasy and purposely alienate the reader. Covenant rapes the young woman, Lena, who welcomes him to her village.

It's as shocking in print as it is in bare summary here. If the Amazon reviews are anything to go by, this kills the book outright for many readers.

To be fair to the author, he doesn't let Covenant off the hook for this. Not only could the first half of LFB be subtitled Self-laceration against a fantasy backdrop, but over the course of the three books Covenant gradually reaps the terrible consequences of his action.

But by destroying any empathy you might feel for the central character, the crime reduces the impact of the central question of the Chronicles: is an illusion worth fighting for? Instead, you get the pop reduction of Covenant to asshole leper hero.

It doesn't help the book, and it doesn't help Donaldson's problems with women in his novels either.

Why you thought this was a good idea I really do not know

The Chronicles actually have a lot of strong women - warriors, Lords, village elders - but when I sat down and thought about it the safest place for a female character to be in Stephen Donaldson's fiction is in the second rank. That way you get to be awesome without stepping into the authorial line of fire.

Let's take a look at the main female characters in Covenant and what happens to them, shall we?

Lena - rape and murder (the second not by Covenant)

Atiaran (Lena's mother) - despair and death by magical accident

Elena (Lena and Covenant's daughter) - killed by a ghost and brought back from the dead so she can be degraded and killed again.

Now that I think of it, pretty much every one of Donaldson's leading women in his other novels gets thrown in a dungeon and tortured - sometimes sexually - at some point or other. None of it is written to titilate, but if he's trying to make a serious point it's eluding me too.

But that's even before we get to the crowning WTF moment of the entire series on book 2, the Illearth War: Back in the Land after weeks of his time and years of their time, Covenant encourages his daughter Elena's sexual overtures to him so she - now a Lord and super-jedi - can take on the role of saviour of The Land and let him off the hook.

????????????

And for good measure

%$&#£@^*&*!

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

I can guarantee you that no-one who gets this far into the trilogy is wondering if Covenant will reconcile his disbelief in The Land with the need to act to protect it. They are all - all of them, darn it - thinking "Dude! This is wrong on so many levels my head hurts"

And these flaws are too big for the reader to ignore.

In writing these reflections, I've discovered that I like the idea of Covenant better than I do the reality. Much as I might appreciate what Donaldson tried to do, as all the bits in The Illearth War and The Power That Preserves without Covenant are great, as the trilogy fizzes intermittently with great ideas, he undermines his own foundations with narrative decisions which seem designed to alienate the reader and cause me to question the merit of the entire project.

Saturday, December 31, 2011

Wednesday, December 28, 2011

The most important failure in modern fantasy fiction Pt 3

Digression - towards a progressive idea of fantasy fiction

The politics of high fantasy - in as far as it articulates them - are deeply retrogressive. While neither Tolkien nor C S Lewis can be simply filed as political conservatives, their works and the works of those who followed them in creating the mainstream of modern fantasy are problematic for the progressive reader.

This is because they fetishise an imaginary medieval.

Humour me while I set up a straw man in high fantasy clothing here. A mediocre author writing in the genre will give you uncritical adulation of monarchy and aristocracy, a poor-but-happy peasantry, nations and species defined by a single characteristic (grumpy dwarf syndrome), fantasy racism (dead orcs don't count), orientalism, patriachy-a-go-go and obfuscatory mysticism.

The classic fantasy happy ending is one which validates any or all of this above. Preferably through a prophecy.

The fact that your setting is pre-modern is not an excuse for any of this if you're making it up.

Good authors can, will and often do subvert these cliches - but in my view most interesting fantasy is being written outside of the genre (wierd fiction, magic realism, science fantasy) precisely because of this millstone.

I don't ask for a politically correct re-imagining of the past, or for Conan to be sent on sensitivity training, but seriously, fantasy writers, the clue is in the name of genre you're writing in.

What does this have to do with Thomas fricking Covenant?

In this context Covenant is interesting because the society he encounters manages to avoid most of the pitfalls I've just outlined.

The people of The Land live mainly in self-governing villages without a trace of a medieval hierarchy. There is no king - there are Lords, but lordship is achieved through initiation into arcane knowledge, training in which is open to all. Men and women alike play leading roles in the villages, the lore-keepers and the military.

Grumpy dwarf syndrome does rear its ugly head with the giants, and fantasy racism with the ur-viles and cavewights existing mainly for plot purposes as sword fodder. But at least the Tolkien xeroxing is kept to a minimum (there are no elves, Galadriel be thanked).

None of the usual grab-bag of forelock-tugging, old-time religion and oppression which usually holds you-haven't-this-through fantasy societies applies in The Land. Instead Donaldson gives us a picture of a people held together by reverence for all that is living, sworn to the healing and protection of the earth.

Whole communities dedicate themselves to the care and mastery of earth and stone, plant and tree, or horses. Other than protecting the Land and increasing their knowledge of 'Earthpower', the Lords pride themselves in their restoration of areas once blighted by Lord Foul.

How many fantasy societies can you think of where everyone swears an oath of peace?

This wierd cocktail of agrarian anarchism, deep ecology and benign academia is there in plot terms, like the geography of The Land, to heighten Covenant's dilemma, to be 'too good' for him. As we shall see, one of the hallmarks of the people of the Land is their refusal to punish him for his misdemeanors (more of which in part 4).

But it also takes us away from the kind of half-baked medievalism of high fantasy into something more like the utopianism which used to be part of fantasy (Cockayne, Shangri-La) before it became the preserve of science fiction and political theory.

The utopian strain running through Covenant is a worthy attempt to use fantasy to put forward some downright progressive ideas about man's relationship to man and nature.

And it's a utopia which had a powerful influence on at least one 90's teenager. When asked, I tell people that the two things which got me into environmentalism were hearing about the greenhouse effect (yes, I really am that old) and reading Covenant and understanding what a reverence for nature and for the achievements of your ancestors could mean in practice.

The politics of high fantasy - in as far as it articulates them - are deeply retrogressive. While neither Tolkien nor C S Lewis can be simply filed as political conservatives, their works and the works of those who followed them in creating the mainstream of modern fantasy are problematic for the progressive reader.

This is because they fetishise an imaginary medieval.

Humour me while I set up a straw man in high fantasy clothing here. A mediocre author writing in the genre will give you uncritical adulation of monarchy and aristocracy, a poor-but-happy peasantry, nations and species defined by a single characteristic (grumpy dwarf syndrome), fantasy racism (dead orcs don't count), orientalism, patriachy-a-go-go and obfuscatory mysticism.

The classic fantasy happy ending is one which validates any or all of this above. Preferably through a prophecy.

The fact that your setting is pre-modern is not an excuse for any of this if you're making it up.

Good authors can, will and often do subvert these cliches - but in my view most interesting fantasy is being written outside of the genre (wierd fiction, magic realism, science fantasy) precisely because of this millstone.

I don't ask for a politically correct re-imagining of the past, or for Conan to be sent on sensitivity training, but seriously, fantasy writers, the clue is in the name of genre you're writing in.

What does this have to do with Thomas fricking Covenant?

In this context Covenant is interesting because the society he encounters manages to avoid most of the pitfalls I've just outlined.

The people of The Land live mainly in self-governing villages without a trace of a medieval hierarchy. There is no king - there are Lords, but lordship is achieved through initiation into arcane knowledge, training in which is open to all. Men and women alike play leading roles in the villages, the lore-keepers and the military.

Grumpy dwarf syndrome does rear its ugly head with the giants, and fantasy racism with the ur-viles and cavewights existing mainly for plot purposes as sword fodder. But at least the Tolkien xeroxing is kept to a minimum (there are no elves, Galadriel be thanked).

None of the usual grab-bag of forelock-tugging, old-time religion and oppression which usually holds you-haven't-this-through fantasy societies applies in The Land. Instead Donaldson gives us a picture of a people held together by reverence for all that is living, sworn to the healing and protection of the earth.

Whole communities dedicate themselves to the care and mastery of earth and stone, plant and tree, or horses. Other than protecting the Land and increasing their knowledge of 'Earthpower', the Lords pride themselves in their restoration of areas once blighted by Lord Foul.

How many fantasy societies can you think of where everyone swears an oath of peace?

This wierd cocktail of agrarian anarchism, deep ecology and benign academia is there in plot terms, like the geography of The Land, to heighten Covenant's dilemma, to be 'too good' for him. As we shall see, one of the hallmarks of the people of the Land is their refusal to punish him for his misdemeanors (more of which in part 4).

But it also takes us away from the kind of half-baked medievalism of high fantasy into something more like the utopianism which used to be part of fantasy (Cockayne, Shangri-La) before it became the preserve of science fiction and political theory.

The utopian strain running through Covenant is a worthy attempt to use fantasy to put forward some downright progressive ideas about man's relationship to man and nature.

And it's a utopia which had a powerful influence on at least one 90's teenager. When asked, I tell people that the two things which got me into environmentalism were hearing about the greenhouse effect (yes, I really am that old) and reading Covenant and understanding what a reverence for nature and for the achievements of your ancestors could mean in practice.

Tuesday, December 27, 2011

The most important failure in modern fantasy fiction Pt 2

Psycho-geography

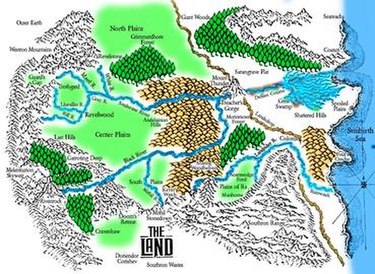

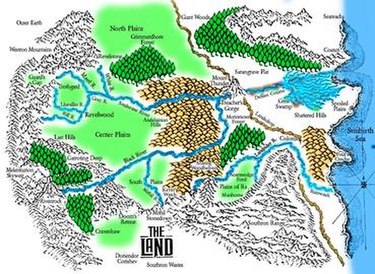

Like most fantasy writers, Donaldson's world-building is shaped by plot expediency and sheer joy in topography and taxonomy. However, that The Land also reflects and partakes in Covenant's psychodrama is a masterstroke

At the start of two of the three books in the Chronicles, Covenant is forced to descend the look out tower of Kevin's Watch. This descent is as much spiritual as physical; it marks his exit from modernity and its entry into a realm begging him to make an apparently simple moral choice to defend it.

Sometimes this plea is verbal, often it is shown rather than told through the beauty of the landscape Covenant sees on his wandering: the Andelainian hills; the pure pool of Glimmermere; the Petra-a-like city of Revelstone. It is even embodied by the 'highest' and 'best' inhabitants of The Land, such as the Giants or the Ranyhyn horse-lords.

In order for Covenant's dilemma to have meaning, this geographical hyperbole is essential. It is vital that The Land be 'too good' for him, ask too much of him.

The creation of The Land through the visual imagination of Stephen Donaldson transcends window dressing - it becomes - and I mean this as a serious compliment - it becomes a stage set which enhances the meaning of the tale itself.

Like most fantasy writers, Donaldson's world-building is shaped by plot expediency and sheer joy in topography and taxonomy. However, that The Land also reflects and partakes in Covenant's psychodrama is a masterstroke

At the start of two of the three books in the Chronicles, Covenant is forced to descend the look out tower of Kevin's Watch. This descent is as much spiritual as physical; it marks his exit from modernity and its entry into a realm begging him to make an apparently simple moral choice to defend it.

Sometimes this plea is verbal, often it is shown rather than told through the beauty of the landscape Covenant sees on his wandering: the Andelainian hills; the pure pool of Glimmermere; the Petra-a-like city of Revelstone. It is even embodied by the 'highest' and 'best' inhabitants of The Land, such as the Giants or the Ranyhyn horse-lords.

In order for Covenant's dilemma to have meaning, this geographical hyperbole is essential. It is vital that The Land be 'too good' for him, ask too much of him.

The creation of The Land through the visual imagination of Stephen Donaldson transcends window dressing - it becomes - and I mean this as a serious compliment - it becomes a stage set which enhances the meaning of the tale itself.

Saturday, December 24, 2011

The most important failure in modern fantasy fiction Pt 1

Yes, as part of my attempt to reboot my reading habits by going back to the old school, I've tackled the First Thomas Covenant trilogy by Stephen Donaldson. This is part one of a four page sanity-preserving peace I'll be writing over the Christmas break. :-)

Warning: this is more reflection than review - but here nonetheless be massive spoilers.

For a proper plot synopsis, see the Wikipedia articles for:

I have the impression - rightly or wrongly - that the Covenant books are something of a Marmite proposition for fantasy fans. For some, they seem to inspire the kind of intense love you can witness at the Kevin's Watch discussion board. For others, the flaws in the series prove impossible to overlook.

But let's start with why Covenant still matters to anyone who takes fantasy fiction seriously.

"Comparable to Tolkien at his best"

The editions of the First Chronicles I cut my teeth on came with this millstone of a quote. In the best traditions of back cover blather, it is, inevitably, completely right and utterly wrong at the same time.

Covenant is many things, but it's most obviously a subversion (and sometimes a celebration) of the clichés of high fantasy which had grown up in the decades post Lord of the Rings. Quests miscarry their purpose. Magic McGuffins lare turned against their users. Sometimes the cavalry doesn't arrive in time.

In particular, the Chronicles takes aim at the John Carter power-trip in fantasy fiction. The all-too-common plot of a modern man finding himself (literally and metaphorically) in a fantasy world, becoming the champion of light against the dark, victorious and loved, is adolescent wish-fulfilment in print. A book has to be very good these days for me to tolerate this trope.

In contrast, Thomas Covenant is a very reluctant champion for the land (named, with endearing/infuriating literalness, The Land) to which he finds himself transported. A grieving writer suffering from leprosy, with intense distrust of himself and others, who has no desire to be the prophesied saviour of another world he barely believes in, Covenant retains his complex modernity in a world of apparently simple moral choices.

To an extent unique in fantasy, Donaldson is concerned with ethics and the problem of acting rightly and is using the Chronicles as a vehicle for exploring his views. Where the comparison with Tolkien holds true is that they are both deadly serious about their respective literary projects.

In the Chronicles Covenant is presented with a very Buddhist or existentialist conundrum: is an illusory but oh-so-seductive world something worth fighting for or a threat to one's integrity as an individual?

Time and time again, the supporting characters of Good - the Lords (think less feudal barons, more medieval Jedi) of the Land and their allies either ask him for aid or present him with yet more evidence of the beauty and virtue of the world to which he has been summoned.

This weight of prophetic expectation is doubled by the 'fact' that Covenant is walking around with the fantasy equivalent of the Pershing missile on his hand - his white gold wedding ring - and has no idea how to use it.

Everything he can do is overwhelmed by its potential significance and his potential responsibility for the Land and the lives of those who live in it.

“And he who wields white, wild magic gold is a paradox For he is everything and nothing Hero and fool Potent, helpless And with one word of truth or treachery He will save or damn the earth Because he is mad and sane Cold and passionate Lost and found”

At this stage in his writing career, Donaldson's prose poetry varies wildly, but I like to think that Albert Camus would approve of this statement of Covenant's potential.

Another recurring factor here is the insistence in The Chronicles - again, rendolent of Buddhist thought - that we are undone by our passions, however noble. The supporting characters in the trilogy may have simplistic motivations in the tradition of heroic fantasy - loyalty to the cause of good, love of nature, pride in service. But Donaldson makes the point - repeatedly - that the extravagance of their virtue leads them into defeat and turns their own best weapons against them.

Got warrior monks (the Bloodguard) in the service of the Land who draw power from their unbroken vow for example? Then have the big bad (a largely shapeless force of corruption rejoicing in the name of Lord Foul) cause them to break their vow and dissolve their order. Simples.

In a situation of such moral hazard, can Covenant be blamed for his caution?

Coming up later in the Christmas break

- Part 2 - Psycho-geography

- Part 2 - Psycho-geography

- Part 3 - Towards a progressive idea of fantasy

- Part 4 - The Many Flaws of the First Chronicles

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)